What excellence looks like

Parininihi ki Waitotara: strengthening ties to whānau and whenua

In the 1970s a collective of Māori landowners in Taranaki banded together to stop the proliferation of Māori land sales in their rohe and protect the land that was left. Determined to take control of their own destiny, they established the Parininihi ki Waitotara (PKW) Committee of Management in 1976 to represent the interests of landowners.

Today, the Māori Incorporation manages 20,000 hectares on behalf of more than 10,500 shareholders. Building from a solid foundation in dairy farming, it has evolved into a richly diverse agri-business with additional interests in crayfish, forestry and commercial property.

While protecting and growing their own assets is core business for PKW, the heart of its role is bringing whānau together, connecting them with each other and with their whenua.

Their vision, "He Tangata, He Whenua, He Oranga" (sustaining and growing our people through prosperity), is as much about spiritual and cultural richness as it is about sustainable profit.

Under the shadow of the confiscations

For many Taranaki iwi, the shadow of the land confiscations of the 1860s is never far away. The name Parininihi ki Waitotara is a potent reminder of the intergenerational devastation caused by the losses. Head of Corporate Services Jacqui King says it represents the confiscation line – and the land they manage within that line.

“The boundary line started from Parininihi in the north and there’s a terrible zig zag which the Crown at the time put in place which confiscated all of our land. That “ki” is the distance to Waitotara in the south,” she explains.

“The Crown mismanaged the land, and it wasn’t until the resurgence in kaupapa Māori in the 1970s that we exerted our rangatiratanga. That movement really drove our owners to come together and regain kaitiakitanga of the whenua that was left.”

Finding a way back to the whenua

Te Poihi Campbell, a landowner from Meremere Marae in South Taranaki, looks out on rich farmland every day, deeply aware of the connections that have been lost between the haukāinga and this whenua.

“There hadn’t really been any relationships with the lands PKW had been farming in this area even though some of the people here are shareholders. Then there was a culture shift within PKW to reconnect with the people on the ground and those are genuine, sincere relationships,” he says.

Every month a small sub-group of PKW hold kaitiaki hui to talk about farm policy. Every quarter a whānau hui is held at a different marae to learn about its history and people.

It took one of these hui at Meremere marae for whānau there to begin to find a way back to their whenua.

“It was the people who recommended we should name the [neighbouring PKW] farms Māori names. That would resonate better with us than numbers like Farm 2 when we were engaging with the lands close by our marae,” Te Poihi says.

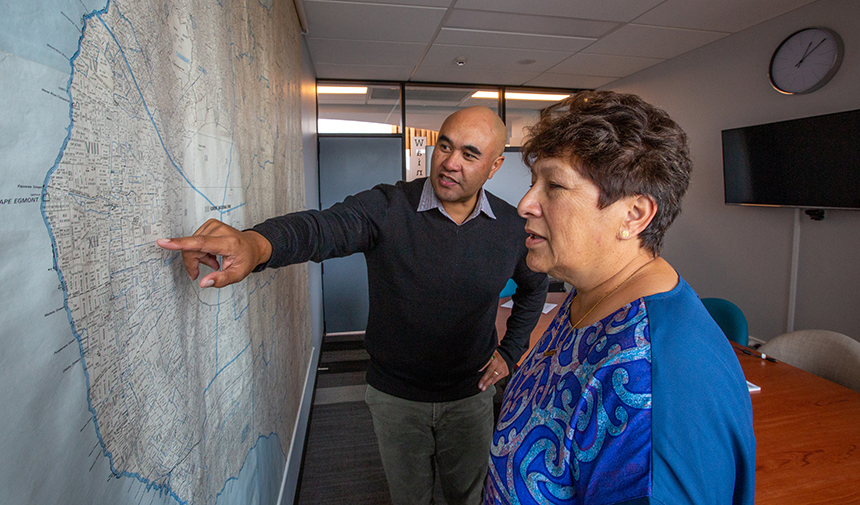

Adrian Poa is the shareholder advisor at PKW, a role he describes as “the best job”. He helps shareholders like Te Poihi re-establish their relationships with the organisation and their whenua. The team also finds opportunities to connect them with the farmers who manage the land on behalf of PKW.

“It’s a beautiful journey for people to be able to walk on their whenua for the first time since the 1880s. It makes the stories of Parininihi ki Waitotara a lived experience.

“Sometimes the share dividend itself is very minimal. Bringing whānau back to the whenua and being able to share the stories about the land is more empowering.”

Te Ruru and Te Kāhu return

Adrian is part of the team that worked with Meremere Marae to name two PKW farms and erect stunning carved signs for everyone to see. They chose the names of birds.

“The very first bird that came to mind as our kaitiaki was the ruru,” says Te Poihi. “There were a couple of kuia who talked about their families’ relationship with the ruru and the area, so it was born of ease which is quite unusual for a marae meeting!”

They decided on Te Kāhu for the second farm.

“The day that we unveiled that particular sign there was a kāhu sitting on the fence waiting for us. That was awesome.”

For Te Poihi the anguish of loss and disconnection resurfaced that day. “It was because my father and my uncle, who have always been standing at the fence of these farms that they belonged to, were able to step on the land."

Then came the unveiling and a way to “restore, recover, revitalise our cultural worth on these lands”.

"To have them there to unveil that particular sign was very significant for our people,” he says, clearly deeply moved.

Re-establishing whānau ties

Many PKW shareholders live away from their whenua. Their journey back is often about finding and reconnecting with whānau – another core function for the organisation and an important part of Adrian Poa’s job.

“Some of them have been away from Taranaki so long they think Parininihi ki Waitotara is an iwi so I go through their whakapapa with them,” he says. “Knowing their whānau ties helps them have a stronger voice when they come back to our hui.”

Cherryl Thompson is the chair of the Hine Rose Whānau Trust, a trust of shareholders within PKW. She started primary school in Taranaki but did most of her growing up in Auckland and now lives in Tauranga.

“I remember our nan coming to Taranaki to meetings. She did this for years until she passed away. My mum was the recipient of the shares and I went to the meetings with her. That was the start of my real journey of reconnection,” Cherryl says.

She recalls aunties and uncles – “I didn’t know how they were connected to me” – turning up at their Auckland home with cheese or fish. “They were the delicacies from ‘home’ that our nanna enjoyed.”

No longer tourists in their own rohe

Cherryl admits feeling lost at the first PKW hui she went to, so she stood back, observed, and tried to take in as much as she could. Over time, and with Adrian and Te Poihi’s help, she’s made connections – so much so that she and her adult children no longer feel like “tourists with a map”.

“Most of the land is in the Hawera district but where it is exactly, I’m still reconnecting to. For us it’s more about the connection with whānau and, lucky for us, we still have some whānau who are on the family land.

“We’ll keep coming back, we’ll keep having reconnections with family. What we’re most excited about is the wānanga we’re planning with Te Poihi who’s going to help us with his knowledge of all the land and the whakapapa. It’ll be a real learning adventure for me and my family.”

Whakapapa endures

As Te Poihi says, whakapapa cannot be severed. It endures through loss and pain. Whakapapa connection – continuing the legacy of the ancestors – is what sustains and drives the Parininihi ki Waitotara collective forward.

“We’ve persevered,” says Jacqui King. “We persevered in the face of adversity and we’ve done that through determination, through resilience.

“It’s a fundamental part of who we are as Māori, but particularly for Taranaki Māori.”